by Peter Callaghan

Given that the financial crisis of 2007 mutated into what one character succinctly described as “a monstrosity that bankrupt the whole of the world economy” and led to over 6 million Americans losing their homes, 8 million losing their jobs, countries such as Greece and Spain hitting the wall and, to date, the imprisonment of only one senior executive (investment banker Kareem Serageldin), credit to director Adam McKay and his co-writer Charles Randolph for turning such a dry and complicated subject matter into an accessible, engaging and hugely entertaining comedy. It’s just a pity that the premonition Steve Carrell’s character Mark Baum has towards the end of the film that in a few years people are going to be doing what they always do when the economy tanks – “blaming immigrants and poor people” or in the words of David Cameron pitting “workers” against “shirkers” – has turned into a sad reality.

When journalists, politicians and so-called financial experts say that nobody saw the financial crisis coming, they are telling truths of a porky pie nature. For as detailed in Michael Lewis’s book of the same name upon which this five-time Oscar-nominated film is based, “While the whole world was having a big ol’ party, a few outsiders and weirdoes saw what no one else could. ”Namely, the bursting of the housing bubble caused by irresponsible lending (in one scene, a landlord who had repeatedly defaulted on his mortgage payments is found to have registered his property under the name of his pet), illegal trading and good old-fashioned greed. The latter prompting an irate Mark Baum to holler at the top of his voice: “How can you sleep at night knowing you are ripping off working people?”

When journalists, politicians and so-called financial experts say that nobody saw the financial crisis coming, they are telling truths of a porky pie nature. For as detailed in Michael Lewis’s book of the same name upon which this five-time Oscar-nominated film is based, “While the whole world was having a big ol’ party, a few outsiders and weirdoes saw what no one else could. ”Namely, the bursting of the housing bubble caused by irresponsible lending (in one scene, a landlord who had repeatedly defaulted on his mortgage payments is found to have registered his property under the name of his pet), illegal trading and good old-fashioned greed. The latter prompting an irate Mark Baum to holler at the top of his voice: “How can you sleep at night knowing you are ripping off working people?”

However, as the author overheard in a swanky Washington bar, “Truth is like poetry. And most people fucking hate poetry.” And so, through a combination of stupidity, arrogance and fraud, the housing bubble swelled and burst as predicted by a handful of “outsiders and weirdos” in the second quarter of 2007, prompting world leaders such as former Prime Minister Gordon Brown (who famously gaffed that he had “saved the world”) to dip into the public purse and bail out the banks to the tune of not millions, not billions, but trillions of pounds. And the real skill of writers McKay and Randolph is making us not only care for these misfits and (partially) understand the complicated jargon they use to justify their actions (in one straight-to-camera cutaway, a busty blonde supping bubbles in a hot tub helpfully advises us that whenever we hear the term “sub-prime mortgages” to “think shit”), but to root for them the whole nine yards as they turn a 50% loss into a 500% profit.

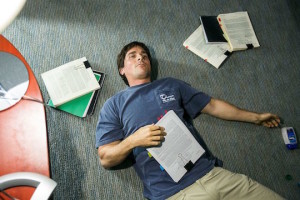

Although very much an ensemble piece of Hollywood A-listers including Brad Pitt, Ryan Gosling and the Oscar-nominated Christian Bale as the glass-eyed loner Michael Burry, the star of the film for me is Steve Carrell who delivers a career-best performance as the grief-stricken Mark Baum who channels his frustrations and rigorous search for inconsistencies in the financial markets into betting against the housing boom. A costly gamble loaded with risk and uncertainty which prompts his incredulous boss to ascertain: “We lose millions until something that never happened before happens?”

Although very much an ensemble piece of Hollywood A-listers including Brad Pitt, Ryan Gosling and the Oscar-nominated Christian Bale as the glass-eyed loner Michael Burry, the star of the film for me is Steve Carrell who delivers a career-best performance as the grief-stricken Mark Baum who channels his frustrations and rigorous search for inconsistencies in the financial markets into betting against the housing boom. A costly gamble loaded with risk and uncertainty which prompts his incredulous boss to ascertain: “We lose millions until something that never happened before happens?”

The score by Whiplash co-producer Nicholas Britell, comprised of original music and a medley of modern hits such as Money Maker by Ludacris and Pharrell Williams, 70’s classics like Led Zeppelin’s When The Levee Breaks and old-time favourites given a modern twist including That’s Life by Nick D’egidio, exudes mischief and swaggers with confidence. And the screenplay, laced with Yes Minster-esque gobbledygook and doublespeak, is a horrifying hoot. As Mark Twain’s prescient quote reminds us at the start of the film, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

[imdb id=”tt1596363″]

- REVIEW: Orphans @ Edinburgh King’s Theatre ⭐⭐⭐⭐ - 13th April 2022

- REVIEW: Everybody’s Talking About Jamie @ Edinburgh Festival Theatre ⭐⭐⭐⭐ - 30th March 2022

- REVIEW: Sheila’s Island @ Edinburgh King’s Theatre - 2nd March 2022